A pen, a passport, a mission for Laos

| Bangkok, Thailand

Colin Cotterill has little in common with his alter ego. For starters, he’s no “ghost doctor.” Nor has he ever performed an autopsy. And yet what would good old Dr. Siri Paiboun do without him?

Mr. Cotterill’s relationship to the wise septuagenarian coroner/medium/sleuth resembles that of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle to Sherlock Holmes. Together, author and protagonist make for a memorable team in unraveling the murder mysteries that haunt their land.

Except in Cotterill’s case, the land is Laos. A small communist holdout between Thailand and Vietnam, it’s a country where books are curiosities: Homegrown literature is almost nonexistent in Laos, and publishing is mostly limited to textbooks.

But now the London-born author is putting Laos on the literary map as a backdrop for his mystery novels featuring an all-Lao cast of characters. He’s also lending a hand in a campaign to distribute children’s books to Lao kids.

“The idea of reading for pleasure is missing in Laos,” says Cotterill, a longtime teacher and child-protection advocate in Southeast Asia and Africa who now lives in Thailand. “Few people even own books.”

Cotterill’s bibliophilic protagonist is no exception. Dr. Siri treasures his battered French dictionary and his antiquated pathology textbook; soon, though, even these perish in flames sparked by a grenade intended for him.

In the novels, Dr. Siri is a latecomer to sleuthing; likewise, Cotterill is a late-blooming writer.

A ruddy-cheeked man with boyish features, a toothy smile, and wavy hair bunched into a raffish knot, Cotterill picked up the pen only a few years ago. While contributing essays and editorial cartoons to Thai papers, he tried his hand at two detective novels, which were published in Thailand. They sold, he quips, “two and a half copies a month at the height of their popularity.... Did I give up? Absolutely!”

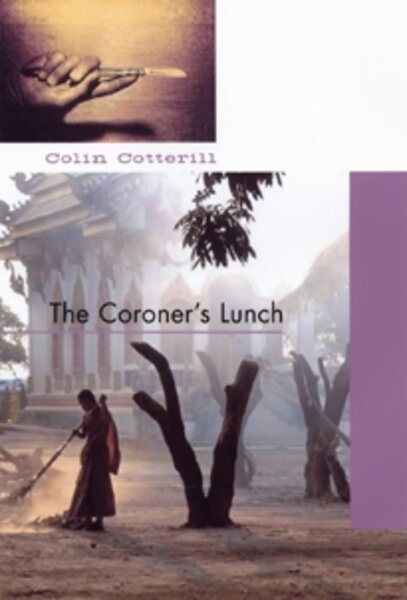

“The Coroner’s Lunch” debuted in 2004, recounting Dr. Siri’s adventures in the turbulent year of 1976: The doctor is appointed state coroner after the Lao royal family has been deposed by the communist Pathet Lao movement, and the professional classes have fled.

To Cotterill’s surprise, the book was an instant hit. “Suddenly all hell broke loose,” Cotterill recalls. “I started to get fan mail and there were reviews in mass-circulation newspapers.” The New York Times Book Review called the novel “wonderfully fresh and exotic.” The book was shortlisted for this year’s Dagger Award by the British Crime Writers’ Association, and Cotterill’s novels have been translated into French, Swedish, Italian, and Japanese.

Last year Cotterill quit his post as a lecturer at Chiang Mai University in northern Thailand to embark on a full-time writing career. The sixth Dr. Siri book, “The Merry Misogynist,” is due out next August in the US, and Cotterill is already working on the seventh.

Along with introducing Laos to foreign readers, the books benefit the country in other ways, too. During a recent tour in the US, the author ended readings by asking fans to help buy books for Lao kids. It was “for Dr. Siri,” he told them.

“Readers can fall in love with a character, and I am the representative of that character,” Cotterill explains. “People are often wary of giving donations to strangers,” he adds, “but in this case it’s someone they know they can trust ... even if he’s a fictional character.”

Indeed, “Dr. Siri” is hard at work in Laos. When he’s not footing the bill for new children’s books, he’s the nominal head of the Dr. Siri Scholarship Program, a fund to help train teachers at a college in northern Laos. Students from remote hill-tribe villages – many of them sponsored by Dr. Siri’s foreign readers – come to learn teaching skills, then return home to start schools in communities where there are none.

“I have a new career thanks to Laos,” Cotterill says. “It’s natural I should give something back. The better Dr. Siri does, the more I can give back.”

In 2003, while doing research in Luang Prabang for his second Dr. Siri novel, “Thirty Three Teeth,” Cotterill was approached by a young girl. She begged for money to buy candy; when he told her sweets were bad for her, she asked for “a little storybook.” Cotterill and the girl trooped around the local market, bookshops, and the printer’s works, but their search turned up only “dust-covered, floppy-backed high-school textbooks,” he says.

So Cotterill launched “Books for Laos,” “importing, mailing and smuggling” children’s books into the country. He had books translated into Lao, pasted translations beside the original text, and gave them to schools and hospitals.

These days he’s donating royalties from his mystery-novel sales to a parallel book-distributing initiative, Big Brother Mouse. The organization, set up two years ago by an American expat publisher and run by a Lao staff, translates, illustrates, publishes, and distributes books for Lao children while also promoting a reading culture. The group already boasts some 70 titles. Staffers also carry books to children in remote villages.

“Often, when Lao kids receive their first storybook,” says Sasha Alyson, the founder of Big Brother Mouse, “they slowly read the first page, then stop. You show them the next page. They read again and stop. When they see there’s more, a smile comes over their face. Incredibly, they’ve never seen a book before.”

•••

Cotterill first set foot in Laos in 1990, when he led a UNESCO program to train new English teachers. But he’d fallen in love with the country years before, in the late 1970s, while teaching Lao refugees in Australia. There, he was captivated by the reminiscences of royalist exiles. Three decades later, one of them – an elderly parliamentarian pining for the ancien régime – would inspire the character of Dr. Siri.

Cotterill’s realistic portrayal of Lao people and their culture has earned him plaudits with reviewers and Lao readers. “The way you tell about life in Vientiane,” a Lao-born émigré historian wrote to him, “is quite extraordinary and most entertaining. Please keep Dr. Siri alive!” In Laos, the first four Dr. Siri books will soon be available in English in local editions; “The Coroner’s Lunch” is being translated into Lao.

“Colin takes some liberties, but remains faithful to Lao culture as a whole,” says Lao-American poet Bryan Thao Worra, who edits Bakka Magazine, a Lao literary journal. Native readers who have read the English editions, he adds, love the books, which “can [also] be a very interesting way for foreign readers to become acquainted with Laos.”

Abroad, some crime-mystery purists have pooh-poohed the novels’ supernatural elements, which include spirits who help Dr. Siri solve murder cases. But Cotterill insists that “you can’t write a book set in Laos without reference to the supernatural.” Local animistic beliefs, which ascribe individual will to plants, animals, and even inanimate objects, permeate daily life in Laos. Ghosts and spirits are considered rampant. In Pakse, a southern Lao town, Cotterill lived in a house said to be haunted by a dead general: “Everyone in the village talked to him and couldn’t fathom how I didn’t see him.”

Like any good sleuth or fiction writer trying to understand the complicated beliefs of this cloistered, idiosyncratic land, Cotterill adds, “I wish I could’ve sat down with him for an interview.”