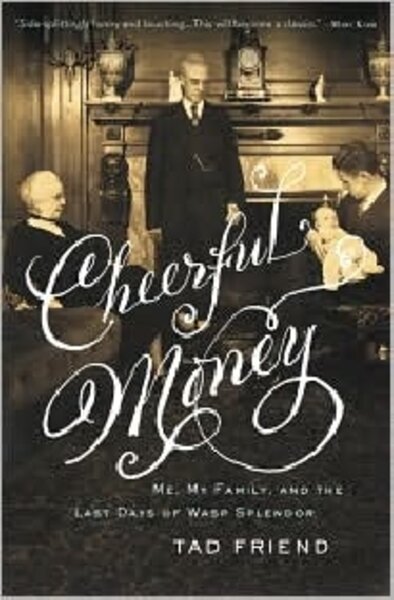

Cheerful Money

Loading...

If you’ve ever felt a sudden, acute desire to casually drape a Shetland sweater over your shoulders even as you complain – just a bit wearily – that you must head out to join old prep school friends at your inherited summer mansion, then you’ve probably experienced WASP envy. (And to be honest, which of us hasn’t felt its sting at least occasionally? After all, Ralph Lauren has made a fortune marketing to such feelings.)

But for those who yearn, there’s now a remedy. Try picking up Cheerful Money: Me, My Family, and the Last Days of Wasp Splendor by Tad Friend. This memoir about what it was actually like to grow up in the inner circles of decaying White Anglo-Saxon Protestant-dom may cause many readers to gratefully embrace even their suburban tract homes and oddly ethnic last names.

Friend is a New Yorker correspondent and, by his own description, the offspring of “a Wasp compass.” When he graduated from prep school, his grandmother’s method of congratulating him was to tell him that she expected “nothing less due to your marvelous background – Robinson, Pierson, Holton, Friend!” Even then, Friend recalls understanding that, rather than a compliment, this was “a eugenic claim.”

Friend’s forebears came to America from England in the mid-1600s and then – on both sides of the family – massively enriched themselves on steel, coal, and banking in the early 20th century. “Briefly,” he writes, they were “smashingly” rich. But one of the lessons a WASP learns early in life, Friend explains, is that “money doesn’t multiply; it divides.... [T]he first generation earns the money, the second begins its dispersal ... and the third [blows] what remains.”

So although Friend grew up surrounded by gifted and privileged people, attending the best schools and immersed in tasteful objects and pursuits, his was a world of “chipped dishes and bitten nails underlying [the] insouciance.” His family was wealthy yet ever conscious of money problems. They summered in the most exclusive preserve of the Hamptons, but drove there in a station wagon with a rusted-out bottom.

Worst for Friend, however, was the unintended legacy passed along by his parents. Burdened themselves by the effects of bad parenting, alcoholism, and a culture that valued the head over the heart, they did their best for their children – and it was better than their own parents had done – but not enough to prevent Friend from inheriting a bad case of excessive reserve and emotional unavailability.

In the hands of a lesser writer, a book like this could read like the empty lament of a poor little rich boy, a tale likely to elicit little sympathy from readers without Friend’s resources or options. (He jump-starts his youthful career with help from the Harvard alumni network and plows $160,000 of family money into therapy. And how many of the rest of us get to take an adult “gap year” to travel the world?)

But Friend’s talents are well suited to his material. He broadens his tale into the chronicle of an entire slice of society and not just that of one cluster of families. (1965, he notes, was the year when it all started to go south for the WASPs.) He also knows enough to keep somewhat of a lid on the self-pity. The tone he strikes is elegaic, even tender (at times) as he chronicles the futile pursuit of gracious living, now sinking into the “ruinous romance of loss.”

“He has many problems, very deep,” wrote one girlfriend in her journal of Friend. She listed his faults as “self-centered, cold, uncaring, and emotionally immature,” counseling herself: “DO NOT HAVE CHILDREN WITH THIS MAN.” Friend’s own father (whom, ironically, Friend accused of excess distance) complained of the “emotional sterility” of his son’s writing. His therapist kept her own catalog of damages: a fear of “intimacy ... imagination ... mess and ... expressing emotion.”

But after years of therapy, marrying the right woman (Amanda Hesser, author and former food writer for The New York Times), and becoming the father of twins, Friend finishes his memoir feeling that he has finally cast off the worst of the starchy WASP legacy.

Perhaps he has, because while “Cheerful Money” is hedged about by a certain chilly intelligence, the pain on display between the lines feels genuine indeed. It’s enough to leave a reader hoping that Friend’s young children will spend their own lives at a healthy distance from the family tree.

Marjorie Kehe is the Monitor’s book editor.