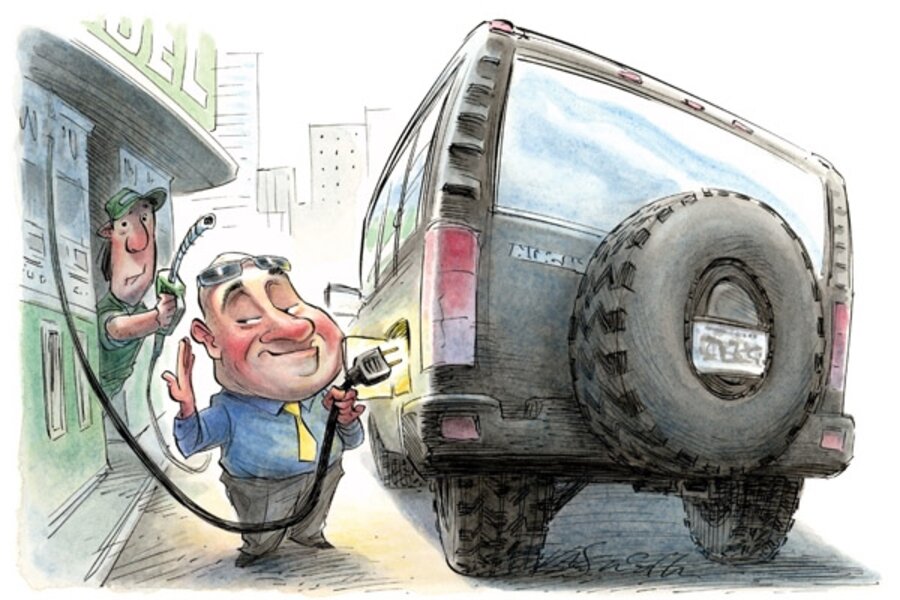

Electric SUVs: A smaller footprint for big vehicles

Loading...

Tom Reid likes his ride big – a 2000 Ford Explorer SUV with plenty of interior room and all the amenities. None of those prissy little hybrid vehicles will do for him.

But after gas hit $4 a gallon last year, Mr. Reid had a big fuel bill, too – and an epiphany: convert his gas guzzler to an all-electric vehicle.

So he did. Now Reid’s bright idea has become a sideline business for his shop, HTC Racing, which produces specialized protective coating for automotive and other metal parts in Whitman, Mass. He offers kits to convert any 1995-2004 gas-sucking Ford Explorer into a cheap-to-keep, no fuel, little maintenance all-electric SUV. Cost: $15,000.

He admits that the idea may be “ahead of its time.” Reid has yet to sell a single kit. With gas at only $2.50 a gallon, the conversion cost is too much for even SUV-loving die-hards. But if gasoline prices soar again, Reid says he’ll be ready – and he won’t be alone either.

Converting America’s vast existing fleet of gas-guzzling SUVs and pickup trucks into electrified vehicles is an idea percolating among policy wonks, start-up companies, and fleet owners such as FedEx and the US Postal Service.

Despite all the hoopla over Detroit’s move to make plug-in hybrid and all-electric vehicles, there’s a need for a speedier US shift away from oil in order to enhance energy security and slow the buildup of carbon in the atmosphere, says a small but growing chorus.

President Obama has set a goal of 1 million plug-in vehicles on the road by 2015. But with 260 million cars, SUVs, and light trucks on the road today, new electrified vehicles won’t arrive in sufficient volume to yield a significant benefit on reducing US carbon dioxide emissions or oil consumption for at least 15 years, says Felix Kramer, cofounder of the California Cars Initiative, an advocacy group that promotes plug-in electric-gas hybrid vehicles.

What that means is that conversions will be needed – and the best place to start is with gas guzzlers, Mr. Kramer says .

They point out that even if all new cars sold in America were electric by 2030, they would only represent a third of US vehicles.

“We’re happy automakers are changing – but new plug-in vehicles sales can’t do the job alone or anytime soon,” he says. “It’s clear [new plug-ins] will initially be a drop in the bucket. So we have to change over existing vehicles – we need conversions.”

A big part of the problem is vehicle longevity. It takes 15 to 17 years for a typical vehicle to go from showroom to junkyard crusher – and sometimes longer for SUVs, pickup trucks, and vans that have sturdier frames.

In the scenario where 100 percent of new car sales are plug-in hybrid vehicles by 2030, US oil consumption would fall by just 21 percent and carbon emissions by 15 percent because of the millions of remaining gasoline cars, estimates a California Cars Initiative white paper.

But with an active conversion program that included tax incentives, the number of plug-in vehicles would roughly double to about two-thirds of the fleet by 2030. That would produce a 36 percent cut in oil use and a 25 percent chop in CO2 emissions.

The reason to focus on gas guzzlers rather than gas sippers is the much bigger benefits from electrifying them. When Kramer of the California Cars Initiative converted his Toyota Prius hybrid into a plug-in hybrid with more electric power – the car went from 50 miles per gallon up to 100 m.p.g. But the United States could save far more, he says, if it converted existing pickup trucks that get 15 m.p.g. to vehicles that can go 30 to 40 miles on a charge before shifting to gas.

And that’s the aim of Ali Emadi, president of fledgling Hybrid Electric Vehicle Technologies, a Chicago spinoff of the Illinois Institute of Technology. His young company has just converted its first Ford F-150 pickup truck from a 16 m.p.g. gas hog into a plug-in hybrid that gets up to 41 m.p.g. gasoline equivalent.

“Our technology could be applied to almost any vehicle from SUVs to pickup trucks, buses, or even school buses,” Dr. Emadi says. “The important issue is that when you apply our technology to larger vehicles – trucks and buses – the fuel economy savings and return on investment are much more attractive.”

Unlike Reid’s all-electric approach, Emadi’s company plans to add an electric drive system to an existing internal combustion engine to create in essence a retrofitted plug-in hybrid vehicle that runs primarily on electricity. But once the battery is depleted after 15 miles or so, it can continue running on its internal combustion engine while recapturing braking energy just like a standard hybrid.

Emadi is in talks with potential customers. Big commercial fleets of pickup trucks, SUVs, and vans seem likely to be the first arena where the economics line up and gas-guzzler conversions get the go-ahead.

FedEx, the big delivery company, began retrofitting some of its trucks to standard hybrid models. But its president, Frederick Smith, says that, in the long term, the company “would likely convert a substantial portion of our fleet to the new plug-in hybrid technology.”

Bright Automotive, an Anderson, Ind., startup, has its sights set on building a new commercial 100 m.p.g. plug-in hybrid van it calls the IDEA. But until it wins funding it is focusing on converting Volkswagen’s Transporter van from a 15 to 22 m.p.g. vehicle to a plug-in hybrid workhorse that goes 22 miles on all-electric and 57 m.p.g. across its 50-mile daily drive cycle.

Earlier last month, Inglewood, Calif., announced it had tapped REV Technologies, a company in Vancouver, British Columbia, to convert its existing fleet of 21 Ford Escape SUVs into all-electric vehicles that get 100 miles on a charge.

“When you just look at the sheer number of cars on the road, they’re not going away anytime soon,” says Jay Giraud, president of REV. “People are saying, ‘I want to keep driving what I’ve got – I just want it to be electric.’ ”

Making a similar point in dramatic fashion, Raser Technologies in Provo, Utah, unveiled a converted plug-in hybrid “extended range” Hummer that gets 100 m.p.g., according to the company. Raser is trying to sell its technology to a manufacturer and has no current plans to convert existing vehicles, a spokesman says.

Which leaves Reid wondering when gas prices will rise high enough that individual consumers begin converting their beloved SUVs, vans, and pickup trucks. He also wonders why those fat federal tax credits of $7,500 for new plug-in hybrids like the upcoming Chevy Volt don’t yet apply to converted all-electric vehicles or plug-in hybrids that accomplish the same fuel savings and environmental benefits. Why not a “cash for conversions?” Kramer adds.

“If the government would help with a reasonable tax credit, you’d get all these entrepreneurs like me converting all kinds of vehicles for maybe $10,000,” Reid says. If gas rose to $4 or more a gallon, he figures his SUV conversion to electric-vehicle kits would be selling like hotcakes.

“The way I see it, Americans have a love affair with their SUVs,” he says. “None of my friends want anything to do with little cars – no matter how high [the price of] gas goes.”