Where do reforms urged by 9/11 commission stand?

Five years after the 9/11 commission made its recommendations for improving homeland security, Congress has overhauled national intelligence and spent billions to upgrade security for air traffic, ports, and other critical infrastructure. But the reform deemed essential to all others - streamlining congressional oversight - never got off the ground.

A staggering 108 congressional committees and subcommittees now claim oversight of the US Department of Homeland Security (DHS). That's up 20 from the 9/11 commission's count of 88 in 2004 - a system it then dubbed "dysfunctional."

Failure to reform congressional oversight has stymied legislation on issues ranging from security for ports and at-risk facilities to seamless communications for first responders.

In its final report, released July 22, 2004, the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States, as it is formally known, urged Congress to create a single point of oversight for homeland security, preferably a permanent standing committee with a nonpartisan staff. It also predicted that Congress would be loath to reform itself - and that without unity of congressional oversight, all other national-security reforms would suffer.

"Few things are more difficult to change in Washington than congressional committee jurisdiction and prerogatives," the report concluded. "The American people may have to insist that these changes occur, or they may well not happen."

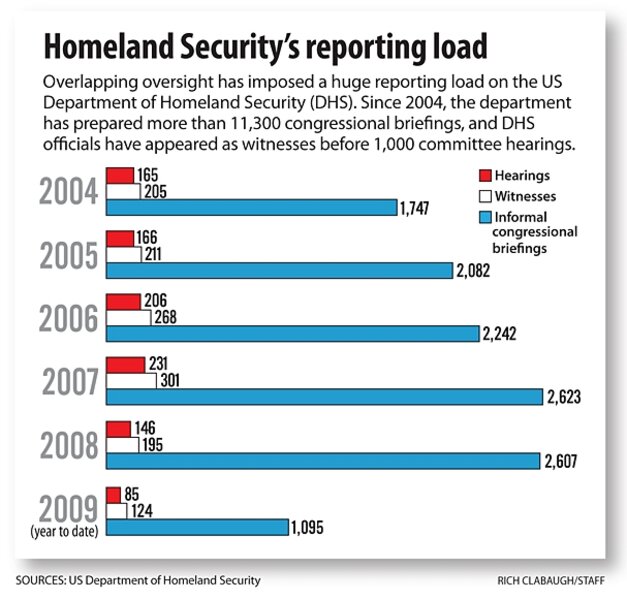

They have not. A maze of overlapping jurisdictions imposes a massive reporting load on DHS officials. Since 2004, the department has prepared more than 11,300 congressional briefings, and DHS officials have appeared as witnesses before 1,000 committee hearings.

Then-DHS Secretary Michael Chertoff complained in 2007 that "the number of very detailed written reports required of DHS by Congress is proliferating at an alarming rate." Many of the 535 annual reports required of DHS take more than 300 man-hours to prepare, he said - on top of some 6,500 less formal requests for information. He pleaded with Congress to "streamline" its oversight.

In her first appearance before the House Homeland Security panel on Feb. 25, DHS Secretary Janet Napolitano reminded lawmakers that "one of the recommendations of the 9/11 commission, the only one that hasn't been acted on, is the need to now streamline and focus on the Department of Homeland Security from a congressional oversight perspective."

Lack of coherent congressional oversight has led to mixed signals and contradictory guidance on several issues vital to homeland security.

The bill that created the new post of director of national intelligence (DNI), for one, was "weaker than it should have been" because the powerful armed services committees kept the DNI from wielding budget authority over Pentagon intelligence programs - a key feature of the 9/11 commission's proposed reform, says Amy Zegart, a professor of public policy at the University of California, Los Angeles.

Turf battles also broke out over 2007 legislation to protect chemical facilities from a terrorist attack. The law mandates that high-risk chemical facilities develop vulnerability assessments and enhance site security. But before the bill made it through Congress, competing committees stripped out whole areas not under the direct oversight of homeland security panels. These include public water systems, wastewater treatment plants, and any facility "owned or operated by the Department of Defense or the Department of Energy, or any facility subject to regulation by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission."

First responders' ability to communicate with one another during an emergency - a top priority after the 9/11 attacks - is another area in which tangled congressional oversight has slowed progress.

"The inability to communicate was a critical element at the World Trade Center, Pentagon, and Somerset County, Pennsylvania, crash sites, where multiple agencies and multiple jurisdictions responded," the 9/11 commission report concluded.

A New York Police Department helicopter pilot circling the World Trade Center on 9/11 warned that large pieces of the South Tower looked precarious, but his warning never got to firemen inside. Their radios couldn't communicate.

Spurred by billions in federal grants since 9/11, states and localities have made progress. About two-thirds of emergency-response agencies DHS surveyed in 2006 report using interoperable communications "at varying degrees."

On July 1, DHS announced the final phase of a three-part testing and evaluation process for the Multi-Band Radio project, which will enable emergency responders to talk with partner agencies regardless of the radio band on which they operate.

But the federal effort to achieve an integrated wireless network (IWN) fell apart last year. The bid to provide seamless communications among the departments of Justice, Homeland Security, and Treasury faltered over disagreements on priorities, according to a Dec. 12, 2008, study by the US Government Accountability Office. The GAO recommends that Congress consider requiring the three departments to work together.

Sen. Susan Collins of Maine, the top Republican on the Senate Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs panel, says the committee intends to address the IWN problem "later this Congress."

"We still have not gotten interoperability worked out - but is it better than it was? Yes," says former Rep. Lee Hamilton (D) of Indiana, vice chairman of the 9/11 commission, in a phone interview.

Some activists who helped establish the 9/11 commission say they're stunned at the difficulties in carrying out reforms they thought were already the law of the land.

"I thought that if it was legislated, it would be implemented," said Mary Fetchet, founding director of Voices of September 11, an activist group on 9/11 issues based in New Canaan, Conn.

After losing her son, who was on the 89th floor of the South Tower on 9/11, she helped pressure Congress to create an independent commission to investigate what went wrong and to ensure it didn't happen again.

"I certainly didn't want another person to perish in the way that my son did," she said in a recent phone interview. "But what I've found is that we had to continue to be involved, because legislation is just the first step."

Without effective congressional oversight and ongoing public pressure, key reforms may never be funded or implemented, she added. "Congress doesn't want to reform itself or streamline the process. There are far too many committees involved in issues that are unrelated to homeland security."

-----

Follow us on Twitter.